Writing well is an art. Mastering it takes a lifetime, and the sharp eye of a keen professional editor can help. But if you don’t have that luxury, you can be your own editor, at least for the small stuff. In this post I reveal a few secret tips that allow you to quickly spot your worst mistakes, and present high quality content, correctly.

Writing an article for your law firm’s newsletter may not fall under the category of professional journalism, yet, employing a few of these editing techniques can get you pretty close.

(1) Avoid fillers.

Fillers are the enemy of good writing. We are all guilty of using certain words, turns of phrase, or structural elements that add nothing to the meaning of a sentence. Your job as the editor is to get rid of them, and produce a final work using the fewest words and crafting the clearest communication.

A filler, or a grammatical expletive, usually begins a sentence with the words it, here, or there, followed by the word to be – it is, it was, it won’t, it takes, here is, there is, there will be. Where it, here, or there refers to something unnamed, or to a noun used later in a sentence, they typically demand extra support words—who, that, and when. All which cause clutter for the reader.

Example:

- “There are some people who seem to have great success in business.”

In this example, there is nebulous and doesn’t add to the meaning, diverting the focus from the subject, “some people.” Better to write:

- “Some people seem to have great success in business.”

It removes three unnecessary words and adjusts to the proper focus.

Be an editor: After your first draft is complete, use the document “search” function to locate there, here, and it. If the sentence also uses who, that, or when, you’ve found an expletive. Re-word the sentence for clarity.

More examples:

- It is important to find good talent.

- Finding good talent is important.

- There are many people who think that…

- Many people think that…

- Here are some things to consider:

- Some things to consider are:

(2) Avoid passive constructions.

To be conspires with it, there, and here in grammatical expletives, and it also weakens construction in other contexts. Your job as an editor is to remove weak construction, also known as the passive voice.

Be an editor: Search and replace to be in its various forms with more powerful alternatives—active verbs.

Examples:

- She is writing.

- She writes.

- People are in love with him.

- People love him.

- Companies are aware that talent is tough to find.

- Companies know recruiting talent is tough.

- He went to Europe.

- He traveled to Europe.

- She tried to make it clearer.

- She clarified her wishes.

In each case, revising the passive construction removes unnecessary words and improves meaning and flow.

(3) Avoid the overuse of nominalization.

To nominalize is to turn a word from a verb or adjective into a noun. In the latter, the result is a vague noun that contains a hidden verb. Writing is clearer and more direct when it relies on verbs rather than abstract nouns formed from verbs. Their use is usually passive, which should be avoided.

You can spot them where the writer adds -ation or –ing to a verb, such as swimming from swim, running from run, legalization from legalize, and nominalization from nominalize, such as used in this subtitle! In most cases, a good editor will swap them for the active usage. Others will find nominalization acceptable in certain context.

Be an editor: Search -ation or –ing and see if it is not better to replace with the active voice. You can also search of. Most sentences that use of are passive.

Examples:

- The experiment involved the combination of the two chemicals.

- The experiment combined two chemicals.

- The citizens were concerned about the legalization of marijuana.

- Concerned citizens do not want to legalize marijuana.

- John completed the race, which included swimming, running, and cycling.

- John swam, ran, and cycled to complete the race.

More examples of common nouns formed from verbs to avoid in order to create a stronger sentence:

- failure (from fail)

- movement (from move)

- reaction (from react)

- investigation (from investigate)

- John conducted the investigation of the theft. (noun)

- John investigated the theft. (verb)

- He shows signs of carelessness. (noun)

- He is careless. (verb)

- She has a high level of intensity. (noun)

- She is intense. (verb)

(4) Avoid weak adjectives.

Certain words like really and very usually precede weak adjectives. Give your writing more impact by avoiding them.

Be an editor: Search and replace really and very.

Examples:

- Really bad = Terrible

- Really good = Great

- Very beautiful = Gorgeous

Also, telling your readers what something isn’t, as opposed to what something is, adds unnecessary words, and worse, can create an overall negative tone to your writing.

- It’s not that good = It’s terrible

- He’s not a bore = He’s hilarious

- It’s not very easy = It’s tough

Be an editor: Search and replace not or isn’t. If you can improve, do so.

(5) Avoid verbosity.

Readers are overloaded with content. Therefore, they typically skim the written word until they find something valuable. Help them by writing succinctly. In other words, don’t be verbose. An objective editor will spot verbosity quickly. But when you are editing yourself, you will have to work a little harder. We all default to common turns-of-phrase that need to be removed.

Examples:

- But the fact of the matter is = But

- Editing is absolutely essential = Editing is essential

- Due to the fact = Because

- The actual fact is that there are more… = The fact is that there are more…

(BTW, unless you’re talking about a “fake news” fact, all facts are actual! Still, I see this all the time when editing lawyers’ work.)

(6) Random acts of kindness to readers (and publishers).

Be kind to your readers. Use the serial comma, the proper pronoun, and one space after a period. And never, ever underline anything, unless you’re typing on a typewriter!

The serial comma. A good editor—you—will use the serial comma, consistently throughout your article, unless there’s a really good reason not to. The serial comma is a weapon against ambiguity. The only reason not to use it is when space is limited, e.g., in print newspapers where every column inch is considered precious. (The Associated Press Style Guide is the only primary guide that eschews the serial comma for that reason.) But generally, that’s not us. A serial comma is used for all items in a series of three or more.

Example:

In the will, Mr. Doe bequeathed an equal portion of the estate to his three children. However, his wishes were written as follows:

- “Susan, John and David each receive an equal percentage of the estate.”

Written this way, without the serial comma, one might assume that Susan receives 50 percent and John and David (together) receive 50 percent. Alternately, if you write

- “Susan, John, and David each receive an equal percentage of the estate.”

it clearly shows the estate being split three ways. There are tons more examples of why we need the serial comma. Deny it at your own risk.

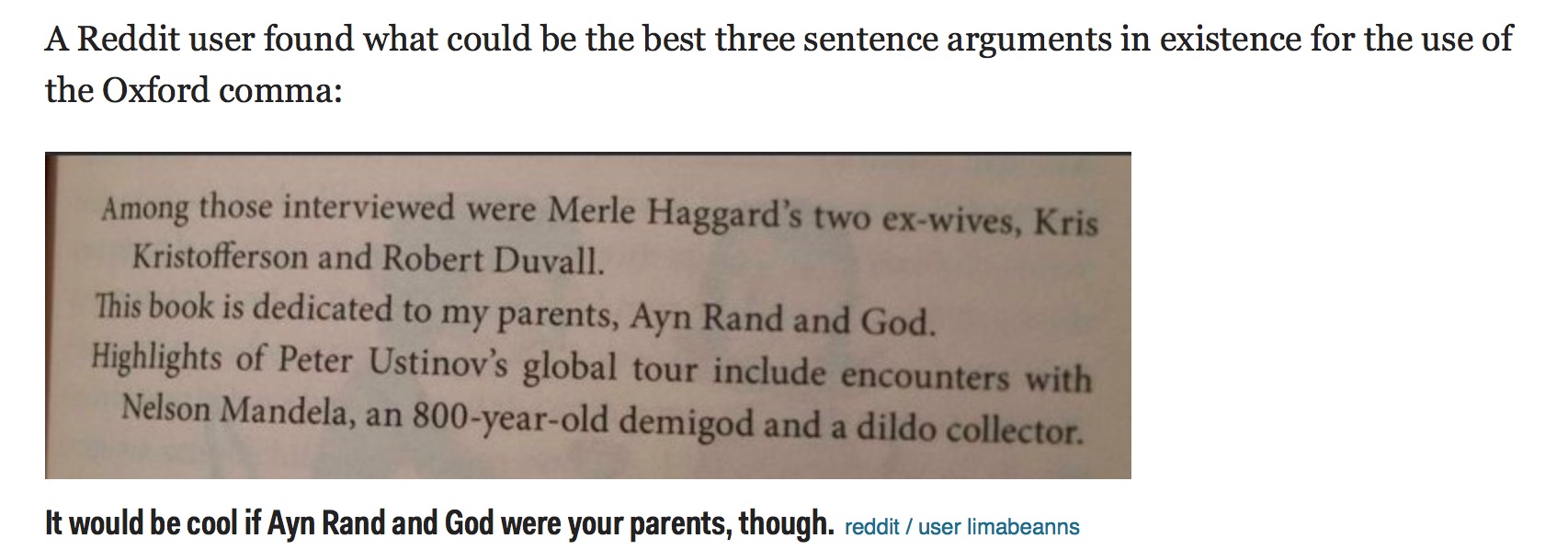

AUTHOR UPDATE: Responding to Bob Ambrogi’s (playful) comment below: Questioning me!! Here are three good examples of when the Oxford Comma is better choice!

The proper pronoun. Companies are not people, except when they donate to political campaigns in the U.S. Therefore, the correct pronoun is it, not they, without exception.

The proper pronoun. Companies are not people, except when they donate to political campaigns in the U.S. Therefore, the correct pronoun is it, not they, without exception.

- “Apple is the world’s largest information technology company by revenue. It maintains 478 retail stores.”

The one space after a period, period! Monospaced typewriter fonts, where each letter was the same width, needed two spaces after a sentence for good readability—period, space, space. Proportional fonts on computers led to the switch to one space (decades ago). So, unless you are writing your article on a typewriter, don’t space, space! Never, ever. Nothing is more frustrating to a professional publisher or editor than having to remove all the double spaces in a document.

(If the court where you file briefs requires double spaces, then you might want to walk them – carefully – into the 21st century. Seriously. If the law school you attend allows space, space, shame on them!)

The underline. Another fall back to the typewriter days is to underline for emphasis. No. Just, please; no. Nothing says “I’m old fashioned,” more than an underlined article title or subtitle because the underline is now used exclusively to indicate a website link. Adding the underline elsewhere confuses the reader.

With italics, bold, and various font styles available on computer word processing software, you don’t need the underline. Editors and publishers will remove any underlined titles, subtitles, or other words in a document that are not links.

- New Georgia Legislation Requires Employers to Provide Healthcare for Domestic Partners

You probably tried to click on that, right!

Finally, most publications and websites follow a custom style template. Best to send them a plain vanilla version of your article with the least amount of formatting possible, in 12pt Times New Roman, 1.5-line space—no underlines—please.

Congratulations! You are now ready to be your own editor. Print this post and keep in your top desk drawer for easy reference—1,2,3,4,5,6.

Be an editor: Check out these reference guides and websites for advanced learning.

quickanddirtytips.com (Grammar Girl)

chicagomanualofstyle.org (Chicago Manual of Style – best for general writing)

apstylebook.com (Associated Press Style Guide – best for news journalists and press releases)

smartblogger.com (A particularly good over all website, well written, with lots of tips for writers, and more.)

Or, if you need immediate assistance, contact the Virtual Marketing Officer for professional writing and editing!

Cheers,

Excellent tips! Thanks for sharing.

What Bob said! An easy choice for our SmallLaw Pick of the Week.

Although I shouldn’t have let her get off so easy with her advocacy for the oxford comma. Why do you need a comma when you’ve already got the conjunction?

We use the Oxford comma. It eliminates confusion more often than not. An em dash or parentheses works nicely when the Oxford comma could cause confusion.

Agree to some extent. I’m a huge fan of the em dash, but not so much as it informs a series. Usually I use it to make a significant break in a sentence–to emphasize. I’m not a fan of parentheses, as I think they are clutter in most cases.

The so-called Oxford comma prevents ambiguity. For example, there is a decision where a will left the residual estate to A, B and C. The court found that A got half and B and C each got a quarter, probably not what was intended. If the will had been written A, B, and C, then each would have gotten a third.

There are numerous other similar holdings.

Furthermore, the lack of the Oxford comma causes the reader to have to read some sentences twice to make sense out of them. Making things hard to read is a great way to discourage people from reading your blog post–or any other document.

Yes. This is, in theory, the Rockefeller Rule, widely disseminated to legal secretaries back in the 1990’s, maybe earlier, but that is where I first learned of its importance. The Rockefeller will was contested and divided as you demonstrate. It just took many years for the general public to understand the importance of what we now call the Oxford or serial comma.